- The Overview

- Posts

- A 2025 Methane Outlook

A 2025 Methane Outlook

5 key areas we’re tracking

NOTE: This newsletter has migrated to substack at https://superpollute.substack.com/

Hi there,

Happy New Year, and welcome to the 15th edition of our newsletter, The Overview: A dispatch on the world of methane and other super pollutants.

Today’s newsletter offers a list of five central topics and themes in methane mitigation we will watch closely this year.

The top line

2025 is, in many ways, a fresh start. While a fresh start can often be a good thing, it also brings uncertainty, and, let’s face it, there is quite a lot to be uncertain about right now. The world of methane is no exception. That said, we are as optimistic as ever that methane mitigation efforts are well-positioned to build on existing momentum and to offer a desperately needed and concrete path to mitigating climate change and slowing warming now.

Here are five key areas within the world of methane we will track keenly in 2025:

Policy tailwinds amidst administrative changes

Data, data, data: Satellites, drones, software management systems, and more

Commercializing solutions: From feed additives to atmospheric removal

Waste-to-value businesses: A durable approach, no matter what

Non-anthropogenic methane emissions

Policy tailwinds amidst administrative changes

The new federal administration in the U.S. that will take the helm in a week or so is clear on its embrace of an “all of the above” approach to energy, including expanding oil and gas exploration and extraction, even as the U.S. is already the world’s leading producer of oil and natural gas. Mind you, the U.S.’s ascent as the global leader in oil and gas production has been a bipartisan phenomenon since the turn of the century; oil production rose 88% domestically under the Obama Admin, too.

Bipartisan alignment on producing more oil and gas aside, it is very unclear whether newer policies like the EPA’s Waste Emissions Charge, which places a fee on fugitive methane emissions from oil and gas operations operating above a specific size of production, will survive the changing of the guard in the White House and changes at other government organizations, such as the EPA.

It’s impossible to predict precisely what will happen with respect to any given policies at this point. That said, there are positive state-level signs that many jurisdictions may retain autonomy to enforce more environmentally friendly policies and subsidies for climate mitigation technologies.

Take the example of California, which has enacted strict vehicle emissions limits and a target of phasing out combustion engine vehicle sales by 2035.

The Supreme Court recently declined to consider challenges against the lawfulness of the state’s right to enact its own more aggressive standards, meaning it’s likely to maintain autonomy in supporting EVs how it sees fit. Denmark, New Zealand, and many other countries and jurisdictions also have targets to reduce methane emissions across sectors, whether oil and gas, ag, or other. Consider, for instance, EU import standards for the methane intensity of LNG imported from abroad.

Turning to other experts, Kevin Birn, an analyst at S&P, recently noted:

I don’t think that the industry is going to go backward from what they’ve learned and put in place…The pressures are not solely isolated or coming from the US government [alone].

Further, Raoul LeBlanc, vice president of upstream at S&P, added:

Companies are taking action, and it’s working…People have gotten after [methane] because of the societal impetus and because of the regulatory pressures — and they now have the tools and the data.

Natural gas storage tanks leak methane if insufficiently monitored and maintained (Shutterstock)

Grounding ourselves back in real numbers, methane emissions in the Permian Basin dropped by ~26% in 2023, according to S&P Global, showcasing that oil majors and other operators of varying sizes already recognize that scrutiny over their emissions is rising and that there’s a business case to keeping more saleable gas in pipelines and out of the atmosphere. Demand for natural gas—the U.S.’s number one fuel source for utility-scale power generation and the power generation source that grew most in 2024 domestically (even beating solar additions on a TWh basis), is rising, keeping more on Earth and out of the atmosphere makes business and environmental sense.

2. Data, data, data: Satellites, drones, software management, and more

Historically, measuring methane emissions has been difficult, and methane-intensive industries have used model-driven emissions estimates (based on frequently flawed or insufficient models) more readily than direct observations of on-the-ground reality in many instances. Case in point: A recent study by the Environmental Defense Fund found that the oil and gas industry in the U.S. has emitted four times more methane than previously estimated by the EPA.

Now, real measurements, whether from satellites or hand-held monitors, can help create baselines against which to measure progress, hold emitters accountable, and quantify which technologies and emissions reduction strategies really work. Better data → better outcomes!

Building off of the data point that methane emissions in the Permian fell 25%+ in 2023, it’s worth highlighting the suite of technologies enabling better, cheaper, more accurate, efficient, and accessible monitoring of methane emissions and leaks, both from oil and gas operations and other sources of methane emissions. 2024 saw several stellar satellites launched into space to offer significantly more robust methane monitoring capabilities:

MethaneSAT: Developed by the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) in partnership with the New Zealand Space Agency, MethaneSAT is an Earth observation satellite that launched in March 2024. Its goal is to monitor global methane emissions with high precision, identifying and reducing methane leaks worldwide. The satellite actively publishes data publicly on an ongoing basis.

Carbon Mapper / Tanager-1: Carbon Mapper is a public-private partnership involving NASA and philanthropic organizations. It is dedicated to pinpointing and quantifying methane and carbon dioxide emissions from individual sources. In August 2024, it launched its first satellite, Tanager-1, to enhance global methane monitoring capabilities.

GHGSat: GHGSat is a Canadian company that specializes in high-resolution remote sensing of greenhouse gas emissions. It operates a constellation of satellites capable of detecting methane emissions from industrial facilities worldwide.

Other monitoring and measurement technologies don’t even need to be sent into space. Many, including Xplorobot’s mentioned above, can be used in the field. Solutions like LongPath Technologies’ laser-based approach and aerial flyovers, whether by drone or small aircraft, can help monitor specific oilfields and areas with significant oil and gas infrastructure. InsightM, formerly known as Kairos Aerospace, also utilizes aircraft-based methane sensing technology to detect and quantify methane emissions from oil and gas operations.

The types of drones that offer monitoring of various pollution types, ranging from gasses to pollution from ships and other air quality monitoring services. (Shutterstock)

Better software management systems for emissions tracking and reporting are gaining traction, too. For instance, Highwood Emissions Management is a Canadian company that provides comprehensive emissions management solutions, including data analytics and strategic guidance, to help organizations monitor, report, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Software systems and management platforms like these—as well as AI applications—that take data from all the measurement and monitoring technologies and organizations outlined above and process it to pinpoint insights and identify actionable mitigation strategies and emissions hotspots to focus on are vital components of the methane mitigation ecosystem.

Comprehensively, all the technologies commercializing to provide better, more actionable data on methane emissions can work in concert to make the successes observed in 2023 in the Permian Basin a common phenomenon in other oil and gas basins worldwide in coming years, as well as for other sources of methane emissions, whether landfills, coal mines, or ‘natural’ methane sources (more on that below in this newsletter).

3. Commercializing solutions: From feed additives to atmospheric removal

Countless individuals and teams are doing groundbreaking work to mitigate methane emissions across anthropogenically-driven and non-anthropogenically-driven methane emissions sources. From companies and other organizations commercializing solutions to methane emissions from enteric fermentation from livestock (see here and here for two quick examples) to researchers evaluating solutions to accelerate natural mechanisms by which methane breaks down in the atmosphere, the work is happening, even if it doesn’t get as much attention as it warrants.

While all these teams do need more funding—methane attracts only a sliver of total climate funding, give or take ~2%—teams and organizations are pressing ahead regardless, often also identifying opportunities where emissions reductions align with economic benefits. For example, for livestock farmers, there’s a growing body of evidence that reducing cattle’s methane production can yield higher conversion rates of caloric intake into meat and milk rather than more methane.

Cattle are the largest anthropogenic source of methane emissions. However, environmental and economic “win-win” opportunities abound, as described in the following paragraphs. (Shutterstock)

Numerous existing strategies include ones like selective breeding, while new technologies like feed additives and vaccines are rapidly commercializing to help reduce methane emissions while improving feed-conversion efficiency (which saves farmers—who operate on slim margins and for whom feed is often line item number one in terms of expenses—money). Confidently, we know of early-stage businesses that are commercializing and scaling quickly to test feed additives that reduce cattle’s methane emissions. We’re talking pilots with major multinational companies that have tens of thousands of cattle under management.

For a specific, publicly documented example, Rupert Murdoch is currently testing a seaweed-based feed additive on his Matador Ranch in Dillon, Montana. In collaboration with researchers from the University of California-Davis, the project will study the seaweed's impact on cattle’s methane emissions. 24 beef steers are being studied, with one group being fed the feed additive while another serving as a control group. Project administrators are even using solar-powered devices to dispense the feed additive and measure methane emissions over the 10-week trial. Pretty neat if you ask us (not to mention another example of bipartisan support for methane mitigation).

We’ll highlight many more examples of this type of work this year.

4. Waste-to-value businesses: A durable approach, no matter what

One of our more recent newsletters late last year covered Emvolon, a company that takes otherwise wasted methane that would warm the planet and pollute the environment and turns it into valuable chemicals like methanol and ammonia. We remain bullish on waste-to-value companies in the methane space, as their business models often ‘work’ independently of significant policy or subsidy support (though those certainly help). If there is value in “waste,” as there so often is in methane that leaks or is otherwise emitted into the atmosphere, there’s often a business case for finding ways to keep it on Earth. Allowing it to escape into the atmosphere is not just environmentally harmful–-it’s economically irresponsible!

Many companies harness the potential of otherwise wasted methane. Emvolon and M2X turn otherwise stranded or wasted methane into useful commodity-esque products and are already generating revenue and gaining commercial traction. Crusoe Energy is also a standout success, as the company recently closed a $600M Series D at a nearly $3B valuation. Crusoe uses flared gas—which is typically not highly efficient at fully combusting methane into carbon dioxide—to power data centers via generators with a much higher combustion efficiency. In 2023, Crusoe reported it prevented 8,500 metric tons of methane emissions while generating over 635,000 MWh of electricity, and its 2024 numbers were likely a significant improvement on that baseline.

In other sectors, such as landfills or agricultural settings, there are ample opportunities to capture and use otherwise wasted and emitted methane. That methane can then be used for many things, whether to make ‘clean’ natural gas (CNG)—which many buses and garbage trucks already run on as part of efforts to decarbonize heavier-duty transportation—or in anaerobic digestors to make renewable energy and meet rising electricity demand while reducing emissions.

Our tl;dr prediction? 2025 will be an even bigger year for companies that take one person’s trash and turn it into profit (and a boon to efforts to slow warming and curb climate change).

5. Non-anthropogenic methane emissions

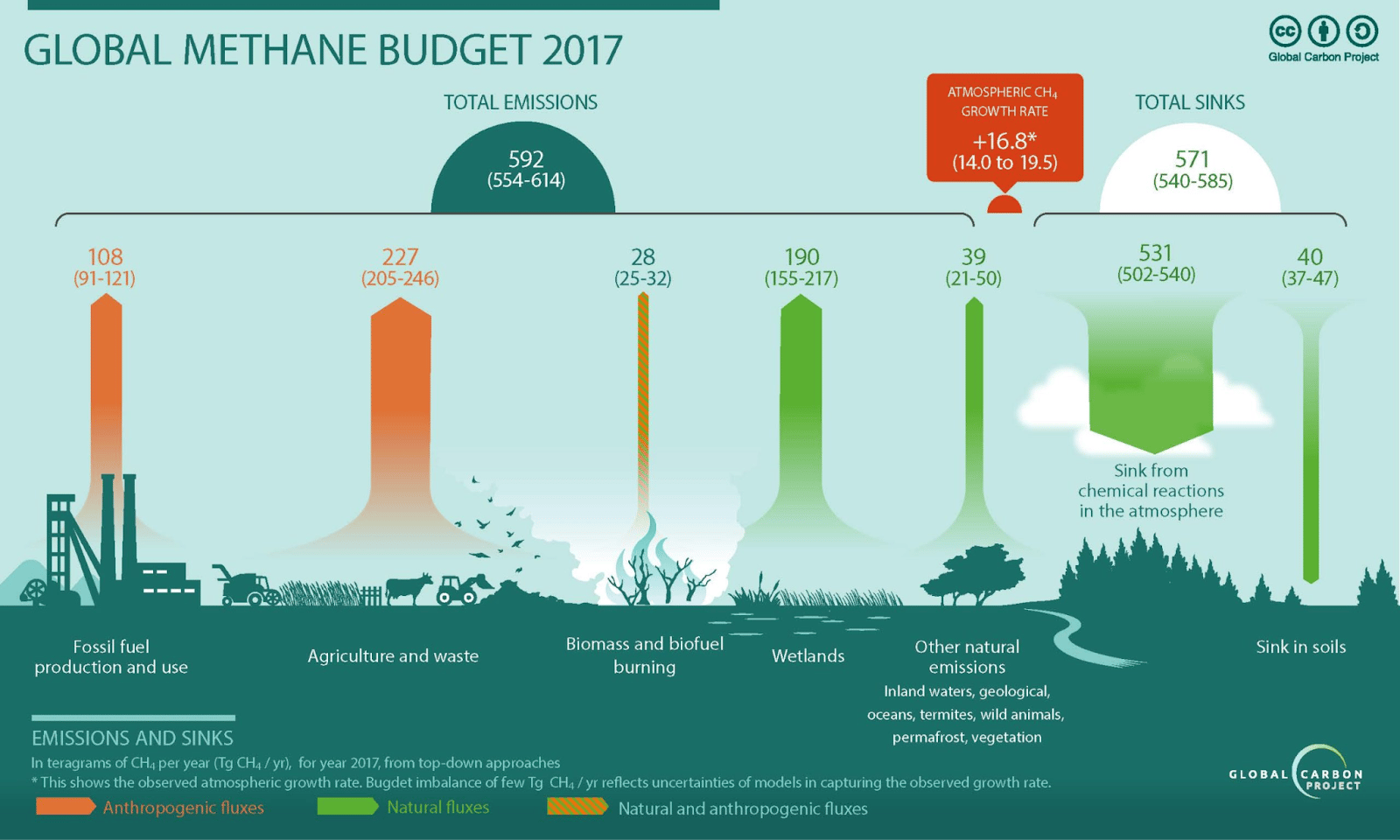

Human-caused methane emissions represent 60% of the additional methane emissions currently heating the planet. The other 40% of methane emissions come from ‘natural sources,’ such as wetlands (the largest contributor) and from wildfires, thawing permafrost, and other sources, like melting glaciers, many of which are fields of very active, ongoing scientific study and research.

The bad news is that as human-caused methane emissions continue to rise, methane emissions from natural ecosystems also appear to be rising (a second source with more information is available here). Problematically, there’s a feedback loop at play here; as greenhouse gas emissions warm the planet, natural methane emissions sources, such as emissions from thawing permafrost, can also accelerate. If left unabated, that’s a dynamic that could become self-reinforcing in a worst-case scenario. Paired with all the other environmental and economic prerogatives to reduce methane emissions, the risks of reinforcing feedback loops increasing natural methane emissions make mitigation efforts for all methane emissions more urgent than ever.

Arctic permafrost thawing in Alaska (Shutterstock).

The good news is that we have tools to reduce the human-caused methane emissions that risk further destabilizing Earth’s climate systems and accelerating the feedback loops that could unlock additional methane from natural ecosystems. Further, to bring it back to the measurement, monitoring, and data conversation, all of the same tools—especially satellites—that support better insight into methane emissions from sectors like oil and gas will be highly supportive in developing a better understanding of where and to what extent non-anthropogenic methane emissions are rising.

All the technologies, solutions, and strategies discussed and within the methane measurement, monitoring, and mitigation universe can work together to get us back to a world where atmospheric methane levels are no longer increasing at all (ideally), or at least not at the alarming rate they currently are (Note: atmospheric methane concentrations have increased more dramatically than atmospheric carbon dioxide levels on a percentage basis since the Industrial Revolution–see below from NASA).

The bottom line

We’re optimistic that 2025 has a lot of positive momentum for methane measurement, monitoring, mitigation, and research and development efforts. What encourages us the most is the community of deeply dedicated and conscientious people in this space who work tirelessly and thoughtfully on all the challenges and opportunities inherent to it. Reducing methane emissions offers tremendous opportunities to slow global warming quickly, drive economic benefits and buffer energy security, and rectify environmental harms in countless communities worldwide.

Keep up the good work, regardless of where you are in the methane landscape or what you focus on day to day. We’re here to trade notes, support you, strategize, amplify news, and learn from you.

— This newsletter is brought to you by Lauren Singer and Nick van Osdol

Reply